[+] HONOURING OUR PATRON, SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL, VICTOR OF THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING PEOPLES

[+] HONOURING OUR QUEEN, ELIZABETH THE SECOND, ON THE 80TH YEAR OF HER BIRTH (1926 - 2006)

[+] HONOURING OUR KING, SAINT EDWARD THE CONFESSOR, ON THE 1000TH YEAR OF HIS BIRTH (1005 - 2005)

[+] HONOURING OUR HERO, LORD NELSON, ON THE BICENTENNIAL OF THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR (1805 - 2005)

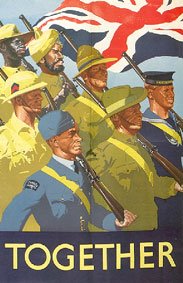

[+] HONOURING OUR SONS, THE QUEEN'S COMMONWEALTH SOLDIERS KILLED IN THE 'WAR ON TERROR'

[+] HONOURING OUR VETS ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE VICTORIA CROSS (1856 - 2006)

ANGLO-FRENCH RELATIONS IN THE DOMINION OF CANADA AND THE IMPERIAL FEDERATION MOVEMENT

“THE KEYSTONE OF THE CANADIAN NATION IS THE FRENCH FACT; the slightest knowledge of history makes this platitudinous. English-speaking Canadians who desire the survival of their nation have to co-operate with those who seek the continuance of Franco-American civilisation”.

It has been written that John Diefenbaker’s great failure as Prime Minister after the Second World War – the last period in which ‘Britishness’ was seen as central to Canadian identity – was his failure to find this milieu for co-operation with French-Canadian conservatism. Between 1958 and 1962, Diefenbaker had fifty Quebec seats behind him, and yet found no Quebecois lieutenants. While it is true that he was unfortunate in the premature death in 1960 of J.M.P. Sauvé, who could well have become the first French-Canadian Tory PM, Diefenbaker’s failure was at root systemic, not contingent. Nor is it true that this failure to engage with French Canada was simply the manifestation of indifference. He, like all other Anglo-Canadian nationalists for more than a century, failed to appreciate that their vision of a united Canada was incompatible with that of Quebec.

This is to say, that Anglo-Canadians’ vision for the Dominion was involved “one united Canada in which individuals would have equal rights irrespective of race or religion…As far as the civil rights of individuals are concerned, this is obviously an acceptable doctrine. Nevertheless, the rights of the individual do not encompass the rights of nations…The French Canadians had entered the Confederation not to protect the rights of the individual but the rights of the Nation”. For them, equal rights in the sense usually implied in British political discourse were a recipe for being swallowed up by an amèricanisme saxonisante. The fact that the rhetoric and practice of multiculturalism in modern Canada has had no concomitant tendency to diminish Quebecois nationalism is a clear indication that this is so – showing respect for the residual customs of ethnic minorities such as Ukrainians and Koreans is one things, but the French-Canadians are concerned with being a nation-within-a-nation, an ambition for which treating every citizen equally would spell disaster.

What this also reveals is that the Quebecois have always shrewdly discerned a fact of which Anglo-Saxons the world over have often been only hazily aware, if at all: that whereas the Cape Dutch, the French Canadians, and other European colonial populations whom the British absorbed into their Empire tended to have no place in their hearts but for their own communities, British colonists the world over always felt part of a far-flung global community whose spiritual centre was the British Isles. From Britain’s earliest attempts at colonisation until well into the twentieth century, millions of people in the British colonial empire who had never, and would never, visit Britain itself continued to think of the British Isles as ‘Home’, tendebant manus ripæ ulterioris amorē.

The fact that the various Dominions’ senses of identity contained this element meant that their nationalism took the form, not of repudiating their Britishness, but of trying to maximise their particular Dominion’s stature and rôle within the British world. Where anti-British nationalism existed in the Dominions, it seldom seemed to conform to the nationalist discourse of the non-settler Empire. In the case of Canada, for example, such anti-British nationalists tended to demonstrate the frustration of trying to eliminate Britishness from public and private life in Canada, while simultaneously retaining something recognisably Canadian, by subsequently becoming Continentalists later on and advocating annexation to the United States – indeed, Diefenbaker’s last speech in the House of Commons before the election in 1963 drew a parallel between the Annexation Manifesto of 1849 and the tradition of Goldwin Smith and the merchants of Montreal on the one hand, and the Continentalist sentiments of rich Torontonians and Montrealers of the early 1960s. He believed that their new approach to Canada’s place in the world was not so much about Canada as about money – only the country with the world’s strongest economy can rely upon the loyalty of its capitalists since their interests are tied to their country’s strength and vigour.

It was not, therefore, until the United Kingdom began to decline as a moral force in the world after 1945 and lost its strength as an alternative pull in Canadian life that a majority of Canadians ceased to think of Britain as ‘Home’, and of themselves as British. Nor had the seductive post-Second World War political fashion, according to which progress is represented as the overcoming of nationalisms and moving in the direction of internationalism, yet arrived to undermine the idea that an exclusively British North American identity was necessary for the promotion of human good.

This concept of loyalty to the idea of British North America meant loyalty to the font of constitutional government in the British Crown. It should be noted that the meaning of this for Canada was far from clear – the allegedly British values of liberty, order, good government, virtue, Christianity et cetera hardly differed from their American equivalents; nor were they ever likely to do so, since Britain and the United States had been separated not because of different values as such, but over the nature of the institutions which would best protect those values. Nevertheless, the British-ness of Canadian-ness seemed sufficiently obvious to most Anglo-Canadians for such problems to be seldom considered.

This would obviously inhibit them from coming to terms with French Canada, but then it is equally arguable that French Canada never made much of an attempt to engage with the values and aspirations of British Canadians. Their adherence to British North America was motivated by the need to hide behind the British imperial frontier to preserve their own nation from the depredations of the United States. This is to say, that the peculiar history of Canada has given rise to two nationalisms, rather than one, and it is no less than arguable that they are mutually exclusive, or, at the very least, in turns antagonistic and defensive.

If Canadian nationalism has historically tended to be divisive, then it is a peculiar kind of nationalism. This, however, raises the important question as to what other kind of Canadian nationalism there could possibly have been, without stretching the ideology of nationhood well past breaking point. A country defined as two cultures in one nation, or more accurately two nations in one state, is not exactly a country in conventional terms, and yet it is this duality or bipolarity which, more than anything else, defines what it is and has always been to be Canadian. This cultural schizophrenia, however, has always been more of a problem for Anglo-Canadians than their French co-nationals: the Quebecois have the most to gain from living as one half of ‘Two Solitudes’, since they have the most to lose from cultural convergence and homogenisation; whereas for Anglo-Canadians the opposite was the case.

As a result, for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, British Canadians sought to ensure that Canada would be a British country with a quaint French province rather than an Anglo-French country. In part, this tradition of isolating Quebec originated in administrative convenience at the time of the conquest. General Carleton, the province’s first real governor, thought that the loyalty of French Canadians was best secured by concession to their traditions and culture. “To Carleton, the answer to Quebec’s future security and prosperity lay in the past…a legislative restoration of all that Canadians held dear in their society, especially the Catholic Church and legal practices based on the Coûtume de Paris”.

An administrative approach to the problem of Franco-American identity, however, covers only a short period of British North American history, before the influx of American loyalists and emigrants from the British Isles changed the Canadian demographic from a conquered foreign province to a British colony with a substantial foreign minority. Already in the 1770s the Protestant merchants of Montreal were clamouring for the Anglicisation of the Quebecois, and with increasing volume after 1784; but as the eighteenth century turned into the nineteenth, and it became clear that French-Canadians would simply not become Englishmen, it made sense in more ways than one to isolate Quebec as a sort of French theme-park and ignore it, confident that they would realise that their least-worst option was the British connection and thus remain loyal and quiet, leaving Anglo-Canadians to consolidate the country as the western bastion of the transatlantic British nation.

An important aside here is to consider the impact on imperial historiography of this particular manifestation of ethnic and national thought and the racial meanings with which they were invested. This serves both to put Anglo-French tensions in Canada within a theoretical framework and to look at that framework from a new perspective. The tendency is usually to assume that racial problems in former British colonies, particularly but not exclusively in Africa, arose from the structures laid down by the colonial authorities when they divided their colonies ethnically, and are therefore a function of the colonial state’s imposed identities.

This, however, is only true if race is considered as part of the social structure rather than a mode of thought; even then, it is more an interplay of meanings than the categorisation and ‘ethnic ranking’ which has attracted so much criticism in post-imperial historiography. Moreover, the fact that, in Canada and South Africa, the same dynamic is clearly visible in relations between British colonists and other white, western European races suggests that the origins of this mode of thought are not necessarily to be found in white supremacy, and that African ethnic nationalists are not thereby betraying their own cultures by promoting a western discourse on ethnicity and nationhood whose original purpose was to enslave Africans to Europeans. This seriously calls into question such descriptions of decolonising nationalism as “not a restoration to Africa of Africa’s own history, but the onset of a new period of indirect subjugation to European history…Liberation thus produced its own denial”.

If, then, racial ideas are not inevitably derived from pseudo-Darwinist raciological doctrines, then they are not necessarily traceable only to the West – they can instead be seen as a field of discourse in which inherited traits and characteristics denote relative moral status between social groups, rendering structuralist or functionalist approaches, like that of Immanuel Wallerstein, less convincing than the idea that race is a universal mode of thought: “the assumption that humanity consists of discontinuous series of authentic cultural wholes, each internally homogenous, the creation and property of a distinct ‘people’” . This is to see genealogy as a kind of half-metaphor for the criteria for inclusion or exclusion from the inherited culture.

Put simply, the division between the concept of nationalism and that of ethnicity or race is artificial, but it has gained currency because it is politically convenient – it is hardly likely to be a coincidence that liberating nationalism, as a native product, is held up as positive, and divisive ethnicity, as an imported European product, like smallpox, as negative. Anything which conforms so closely to the legitimacy/illegitimacy paradigm of post-colonial historiography is almost certainly too simplistic. Paradoxically, this both allows colonial apologists to abrogate much of the responsibility for continuing ethnic-national violence in post-colonial societies, and also liberates those societies by jettisoning the assumption that the violence from which they suffer arose from the structures laid down by colonial authorities.

In any case, structural or functional approaches fall somewhat short of explaining the bipolar nationalism of Canada. For example, nationalism as a product of a certain kind of complex and dynamic labour division within a geographical area is inadequate when considering two nationalisms within the same industrialised geographical area. For the purposes of this paper, the less tangible – or at least less precisely calculable – ideas of providence, destiny and related quasi-religious senses of identity, which are as much part of societies’ attempts to link each generation with its predecessors and successors as is the continuity to be found in religion per se, will be considered above and beyond the dry imperatives of the industrial economy, or the homogenising tendencies of economic integration, or any of the more unedifying materialist approaches to nationhood.

If one pillar of this essay is the nature of the Anglo-French relationship within the Dominion of Canada, the other is the nature of the relationship between the United Kingdom and the Dominion. The argument shall be made that, together, these twin pilasters bore aloft the great superstructure of Canadian imperialism – a sentiment which in Britain was more usually described as the movement for Imperial Federation. More specifically, it will be argued that the functions and meanings of the British connection for Anglo-Canadians was dependent on, and altered by, the ‘French Fact’ in a manner which, in its own way, was as significant for Canadians’ attitudes towards their place and their rôle in the world as was sharing a border along the forty-ninth parallel with the Manifest Destiny.

CHAPTER II.

THE THEMES OF CANADIAN RELATIONS WITHIN THE BRITISH EMPIRE and, more particularly, with Great Britain, in the later nineteenth century have been described fairly consistently by most historians of imperial unity. These may helpfully be summarised as three main elements in Canada’s search for a national direction: American pressure, Canadian needs, and British support. These elements were all intrinsically linked, although different authors have tended to give weight to this or that particular strand.

Norman Penlington, for example, has emphasised considerations of the USA as the most important driving force behind imperial solidarity. “Imperial federation…meant the orientation of Canadian policy towards Britain for the attainment of specific political and economic purposes…to defend the Dominion against the US” – a sort of Anglo-Canadian parallel to the French-Canadian imperative for loyalty. In this context, the confederation of 1867 is seen as a response to American expansionism following the Civil War – a strong motive for national unity, but one which could only be achieved with British help to solve the myriad problems involved in such a political consolidation, making the connection with the United Kingdom crucial for Canadian survival. This theme is taken forward into the post-confederation period, as the USA abrogated the Reciprocity Treaty, failed to prevent the Fenian Raids of 1870, made sotto voce threats to annex the Canadian west during the Red River crisis in 1869, and so on. In the latter case, it was only the British military expedition which saved the Dominion from falling apart.

Given that the British connection was crucial to Canada in a dangerous situation, it is not surprising that the Anglo-American Washington Treaty of 1871 – which was presumed to demonstrate that Britain cared more for its position vis-à-vis the USA than the defence of Canadian interests – caused widespread fear that Britain was keen to disengage entirely from North America and leave Canada at the mercy of the Monroe Doctrine. Some even suggested that Britain’s only interest in Canada was its usefulness in Anglo-American relations: bits of it could be given away to appease the Americans, as had been the case in Maine, Ohio, the Upper Mississippi and Oregon. As a result, what the exigencies of Canada’s position in relation to the United States required from Britain had to be presented with imperial justifications. In terms of westwards expansion, for example, British Columbia had been induced to join the Confederation with the promise of a railway, and in order for the railway to be worthwhile, extensive settlement was needed. Only Britain could supply the money and people to bring this plan to fruition, and thereby prevent the USA from expanding into these territories. Thus, Canadians pleaded the imperial necessity of a ‘Red Route’ to the East, and that a prosperous Canada was good for the British Empire.

Canadian nationalism, therefore, had of necessity to be linked to British race patriotism; the imperial connection had to be strengthened as a source of unity within Canada; and eventually some form of imperial Zollverein was seized upon as a means of diminishing the relative importance of North-South trade and thereby marginalising support for Commercial Union with the USA. In every sense, then, Canadian imperialism is reduced to “a counterpoise of Canadian-American relations”. Indeed, Penlington’s argument would have carried even greater weight had he emphasised not merely the immediate problems presented by a large and bumptious neighbour, but also the sense amongst Canadian imperialists that the United States were the antithesis of all they stood for, i.e., the ideological rejection of Yankee republicanism which had been latent in Canadian identity since 1784. In this context, the monarchy became a focus for national identity; ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ was derided as levelling and socially atomising when compared with the ‘peace, order and good government’ of the Canadian national mission – indeed this latter was written into the Canadian constitution by the British North America Act in 1867 as a general power, along with thirty specific legislative powers, to pass laws according to this flagship principle.

Be that as it may, the ‘American model’ of Canadian imperialism sees this American pressure coinciding with more favourable British responses as the relative weakening of its own position inspired a new desire to maintain, expand and consolidate imperial power. Enthusiasm for the Canadian preference, Liberal Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier’s reception in London for the Jubilee and so on reinforced the idea that the days of British disdain for protestations of colonial loyalty were over, and gave encouragement to those who believed that the development of the Dominions required changes in imperial organisation, since the status quo was unsatisfactory and integration or independence the only alternatives.

To this extent the model is correct – the mid-Victorian belief in separatism was coming to an end by 1870, as the factors which had given rise to it were unravelling. The conviction that colonial emancipation was desirable was based on out-of-date assumptions: that independence was inevitable; that there was therefore no point in wasting resources putting it off for another day; that in Canada’s case it increased the danger of war between the UK and the USA; that free trade made the colonial link economically pointless, and that, even without free trade, commerce with the United States had been more profitable after independence; that emigration as a domestic social function would take place without a constitutional connection and that colonial wastelands were no longer in the hands of Parliament in any case; that the colonies would never send troops to help the mother country, but would demand British troops when threatened; and that the vindictiveness which had embittered Anglo-American relations had to be avoided in future, and that this could only be achieved if future partings were not in anger. According to C.A. Bodelsen, the paradox of this situation was that it gave rise to the doctrine of benign neglect which itself contributed to colonial loyalty, as indeed had been the case with the American colonies until the 1750s. “The liberal policy of…constant yielding to colonial demands, to which the continuance of the connection is largely due, was greatly facilitated by the belief that the connection was in any case bound to come to an end in some not too distant future.” As the assumptions outlined above lost ground, and the policy changed from indifference to active interest, it was not beyond the bounds of possibility that the opposite situation would obtain, and the loyalty of the colonies would be undermined.

And indeed these did lose ground, and very rapidly. Extremist movements tend to bring about a reaction to themselves in any case – les pères ont toujours tort – but the situation in Britain itself was giving rise to an increasing emphasis on the imperial rather than global aspect of British power. Prophesies of inevitable separation were proving increasingly hollow, and after the gradual troop withdrawals from 1862 the colonies were costing less to defend anyway; war was looking less likely with the USA as the Fenian threat died down and the Northern States became less boisterous after 1865; the irrelevance of administrative boundaries in a world of free trade seemed old fashioned as Europe and America were turning to protectionism as a tool of national policy; the Manchester School’s ideology was isolated in the mid-Victorian zenith when competition was negligible, and the rise of America and Germany, after the Civil War and Unification respectively, both heightened competition and caused many to think that devolution was going against the grain of world political developments in which states were coalescing into larger blocs. As a result, when Gladstone’s first ministry seemed to be trying to cut the colonies adrift by withdrawing troops from New Zealand actually during a Maori uprising in 1868, he unwittingly lit the fuse of a new imperialist movement. “Before 1869 separatism had been in the ascendant, after that year imperialism was steadily gaining ground.”

At this stage, the new movement remained very much a London phenomenon. The Royal Colonial Institute was established and various influential voices were recruited for the imperialist cause, such as Liberal statesman W.E. Forster and historian J.A. Froude. The latter’s essay, England and the Colonies, was directly prompted by the sense that the administration was separatist, and dealt extensively with the social importance of imperialism: a 100% urban population was undesirable, and emigration to the colonies was necessary to preserve the rural element in British life, which meant that émigrés had to remain Englishmen after emigration, and so the colonies must continue to be part of the British nation. From 1871, when Edward Jenkins published his two articles on imperial federation, the emphasis moved away from stopping the break-up of the Empire and towards the reversal of existing devolution – in other words, it became an offensive rather than defensive movement and thereby took on a new character. Benjamin Disraeli’s Crystal Palace speech of 1872 suggests three things: firstly, that the Empire had become an element of party politics; secondly, that the movement had achieved a firmer standing in political thought as “part and parcel of mid-Victorian respectability”; and, thirdly, it reflects the popularity of imperialism, since Disraeli’s earlier well-known contempt for the colonies did not speak for strong imperialist sentiments, but rather the ability to spot an electoral asset when he saw one.

Moreover, as the British stopped to take stock of their position in the world in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, what they saw was not, perhaps, what they expected. Looking at the panorama of a vast Empire, it suddenly seemed as if the keynote of British history was not the constitution or the Corn Laws, but overseas expansion. If, as John Seeley argued in his seminal Expansion of England in 1883, history was the school of statesmanship and the best political teacher, and as such the past was the key to the present and guide to the future, then when the Whiggish historical emphasis on constitutional development through the battle between liberty and authority was discarded as the central element of British history, and replaced by the transition from island race to global hegemon, imperialism of necessity became a central element in British political thought.

These, of course, are entirely Anglocentric aspects of the imperial movement. Nevertheless, all this added up to a more fertile ground for imperialism in political thought and a more receptive ear in London to parallel colonial developments, and Canadian ones in particular, which brings us to the analysis of J.E. Tyler. According to Tyler, imperial federation, which was by no means unchallenged in the United Kingdom, let alone the colonies where it enjoyed less widespread support, was a vague call for unity in some form in response to a temporary crisis. In Canada, this involved the end of the railway boom, the loss of people from the North and West rather than the attraction of mass settlement, economic stagnation from the 1880s, and the haemorrhaging of people to the USA to the extent that a third of all Canadian-born people were living south of the border. This model of Canadian imperialism sees a crisis in the Canadian position in North America as coinciding with a crisis in the British position in the Concert of Europe, leading to a temporary harmonisation of British and Canadian interests in strengthening the ties between the countries of the British Diaspora.

In the Canadian context, the crisis presented a stark choice between ‘commercial union’ with the American republic and imperial unity. Commercial union, of course, was not without its supporters – most notably Goldwin Smith, former Oxford professor, Manchester School Cobdenite and arch annexationist. As a coherent movement, it can probably be dated from 1886 as the contraction in trade, markets and profits made it easy to extol the virtues of doing anything possible to encourage North-South exchange, to end boundary and fishing disputes with the Americans, and to talk up the supposed successes of the reciprocity period before 1865. Tyler argues, however, that this would have not only have been contrary to Canadian sentiment, but also not in Canada’s economic interests, as they sought to protect their nascent industries from developed American competition, just as the USA had sheltered American industries in previous generations. Indeed, Alexander McNeill, a contemporary observer, although by no means impartial where this issue was concerned, went so far as to describe Goldwin Smith as “an interesting relic of a bye-gone time”.

Moreover, the Americans’ dominance of such a pact, combined with their messianic belief in their own destiny – which, perhaps, seemed more dangerously deranged at the time than it does in retrospect – would have meant inevitable incorporation, which tended to turn Canadians towards the Empire for various reasons. In the first place, Quebec would never support it, since the Americans would be far less tolerant than Anglo-Canadians of their culture. The unfortunate Acadians – who had fled from Nova Scotia to Louisiana after the British conquest of Canada in order to preserve French North America – had been incorporated into the independent Unites States a generation later and found that their culture, language and religion were subject to pressures which the British were neither willing nor able to bring to bear on French Canadians who had stayed behind. Secondly, for British and French Canadians alike, it was clear that London would always allow a longer leash than Washington, however integrationist Britain became. Thirdly, unlike the American alternative, simple geography meant that closer economic and even political relations with Britain could never lead to outright absorption. So, while annexation was just what it appeared, and independence would lead to annexation as “la seule eventualité probable” in any case, the logical course was to entrench the imperial connection.

In putting forward this model of imperial federation as a Canadian response to a crisis coinciding with a similar British response to a different crisis, Tyler argues that the nature of the Canadian response was to be understood in two contexts: firstly, the United States, as outlined above; and, secondly, French Canada. His treatment of the second consideration, however, is fairly brief. He describes the Quebecois as introverted, parochial, and consistently opposed to imperial federation when they thought about it at all. Anglo-Canadians assumed that they were loyal because the only alternative to the British connection was the obliteration of their identity by Yankee republicanism. This, however, is a support for the status quo, not for imperial federation. The protestant, Francophobe element of Canadian imperialism is briefly raised through the window of the Equal Rights Association, which was established in reaction to the Jesuit Estates Act and was basically a no-popery movement masquerading as an anti-ultramontanism movement, and its leaders were all prominent members of the Imperial Federation League. This, however, raises questions without answering them, especially in conjunction with the consistent French-Canadian belief that imperialism was an Anglo-Canadian conspiracy to eliminate the French element in Canadian political life, and thus leaves a potentially revealing aspect of Canadian imperialism unexamined.

So far, imperial federation has been described as a response to American pressure, to a revolution in British geopolitical objectives, and to crisis within Canada, in which the possible alternatives were independence and imperial co-operation. Independence, for various reasons, was discarded – principally Canadian considerations of the United States and the Quebecois. These, however, were all different motivations for finding a new modus vivendi, which is why it is hopeless to talk of ‘colonial attitudes’ in general. Imperial federation, depending on what each colony actually wanted from the Empire, could be a Zollverein or Kriegsverein or even complete Vereinigung; it could be symbolic or material, loose or tight. Carl Berger, however, has described how forces within Canada, rather than external circumstances on their own, helped to shape the loose body of attitudes which became known as imperial federation.

Berger argues that “imperialism was one form of Canadian nationalism”, based on Canadians’ sense of history and their future mission, the latter forming a strong desire for a significant post colonial rôle. The core of this movement were the United Empire Loyalist community of Toronto, who believed that Canada originated in the belief in imperial unity, and therefore that the fact that Canada played no rôle in the Empire as a whole was an illogical and unjust. Imperial federation in this sense, then, was both reactionary and progressive: what Canada was in times past dictated what it should be in times to come. This was a symbiosis of pride and anticipation rather than Anglophilia per se, since impatience with the sense of subordination to Britain was a central element of it. The emotional attachment to Canada and the desire to see her as a significant force in the world led them to believe that Canada should share in the responsibilities of a world empire: the redemption of Africa, the spreading of liberties, bringing law, order and enlightenment to the dark places of the Earth, and all the familiar themes of the New Imperialism. With it went Tory nostalgia, hand-in-hand with the social imperialism of some British federalists, which rejected the capitalist calculus and extolled the rural way of hands-on living – a country was not merely “a geographical expression” or a “money-making machine”. Charles Mair, the unofficial poet laureate of Canada First whose lines appear at the title page of this paper, was particularly keen to emphasise this, writing:

[B]ring me dreams of love,

Dreams of by-gone chivalry,

Wassailing and revelry,

And lordly seasons long since spent

In bout and just and tournament.

According to Berger, it was this element which was primarily responsible for its failure. The appeal of this Romantic conception of society – propagated by people whose ancestors had represented themselves as American cavaliers to the Yankee roundheads – was too narrow, and indeed in opposition to the most powerful forces in Canada around the turn of the twentieth century. For example, for these people, imperial free trade was just a means of imperialism – as good a way as any for consolidating the Empire and for symbolising the British world’s united front contra mundum – but industrial interests in Canada were hardly likely to share their market with more developed British competitors any more than with their American counterparts through Commercial Union with the USA. The Americans had protected their industries and thereby diversified away from the ‘colonial’ economic relationship, i.e., providing raw materials in exchange for manufactures. It was to achieve the same that Canadians wished to diminish the importance of the North-South economic relationship, and so an alternative imperial relationship which would have the same effect was not an attractive option. Canada would, in such a way, perpetuate her subservience, which exactly what the imperialists wanted to prevent. They failed to see that people are not generally inspired by sentiment to material sacrifice, especially when that sentiment is far from universally shared.

Berger’s model, then, is of an imperialism not concerned “only with the relative economic merits of alternate commercial policies, but with history, tradition, power, and religion”. This, however, is not in opposition to considerations of American ambitions, or to a sense of national crisis; it is, rather, a complementary strand of internal Canadian developments which, converging at the same moment with other forces both in Canada and in Britain, goes a long way towards explaining the sudden craze for imperial federation and also its eventual failure. American pressure would not be focused on the same place for ever, national crises tend to be temporary, British priorities were and are notoriously capricious, and the leading imperialists of Canada had seized upon an imperial means to achieve objectives which many Canadians did not share.

What is not suggested is that its failure was the result of one of the elements which made it so popular – it would enable British Canadians to diminish the presence of Quebec within the political life of the Dominion. Given that the descendents of the United Empire Loyalists so firmly believed that they were Canada, it is important to understand who they were, both according to their own estimations and according to objective reality. Canada, according to their world-view, had come into being in reaction – their reaction – to the American Revolution. Significantly, however, their most prominent personalities were never die-hard supporters of North’s parliament, but patriots who, like all other patriots, had supported the Crown but opposed Parliamentary taxation. They only drifted away from the rebel camp after the Declaration of Independence and often even later.

Such people included William Smith, patriot and Whig, and in 1780 Chief Justice of loyalist New York; William Samuel Johnson of Connecticut; Peter Van Shaak of New York; Daniel Leonard and Benjamin Church of Massachusetts; Andrew Allen of Pennsylvania; Robert Alexander and Daniel Dulaney of Maryland; not to mention the famous Philadelphia turncoat, Benedict Arnold. What disillusioned most, if not all, of these United Empire Loyalists was the rejection of the Carlisle Commission, which conceded every American demand up to 1775, in order to secure the alliance with France in 1778 – a fact made explicit in Arnold’s apologia to the American people explaining his defection. Seen from this point of view, Canadian imperialism seems less like a means of consolidating and strengthening a single country composed of two nations than an unrealistic, last-ditch attempt to preserve a culture which had been blown out of North America at Saratoga and Yorktown – just as French Canadians sought to preserve a Franco-American nation whose independence had been destroyed by Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham.

If, then, Francophobia and anti-popery were at the very heart of the UELs’ origins and identity, and given that the UELs were the ideological core of Canadian imperialism, it stands to reason that the incorporation of a substantial French Catholic population in their new country posed significant ideological problems and loomed large in their political agenda for Canada. For example, in the context of the modernisation of the militia for which they incessantly campaigned, the often-emphasised loyalty of the Quebecois was quite clearly of a certain type only. In 1776 and 1812, they had taken up the defence of Canada against the United States, whose record, as has been seen, did not inspire them with confidence that their antique form of pre-revolutionary peasant French would be accepted as a legitimate language in Congress. After all, it was American horror that French civil laws should be allowed to the French Canadians under the Quebec Act which been the tipping point for many Americans’ turn against Britain, including those who later rejected the revolution which they had helped to start and became UELs.

This, however, was clearly a defence of the Quebecois’ own interests when threatened by invasion – if, on the other hand, the Americans looked likely to annex the North and West of Canada, it was not so obvious that they would be remotely interested in defending it. As a result, the French Canadians’ sense of their messianic mission to preserve the True Faith in North America was no help at all to British Canadians’ equal sense of messianic mission to preserve royal authority in North America, and would thus have to be educated into the redemption of the world through the medium of the British Empire. Pride in the achievements of a shared Empire might inspire them out of their cultural introversion, which undermined Canadian national unity and hence weakened the country. If this were achieved, they may be prepared to contribute not merely towards defence against the United States, but also to the imperialists’ project to create a strong, self-sufficient country which could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with both the USA and the UK.

Perhaps paradoxically, the importance of defending the North West itself was predicated to a large degree in minimising the French political influence in Canadian national life. The influx of millions, perhaps tens of millions, of British immigrants to the empty spaces would reduce the French Catholic proportion of the population as relative to the British Protestant population. That Canadian imperialists’ persistent agitation for assisted British emigration programmes to these regions were not merely part of their programme to make Canada into a great nation is belied by the fact of their repeated assertions that the dual-system of the French provinces should not be extended to the western territories, and that they should be reserved for Englishmen, English laws, and the English language.

Similarly, as it became gradually clearer that the Pacific and Arctic provinces were not attracting mass immigration as the imperialists envisaged, there is a case to me made that the turn towards imperial unity was inspired in part by the fact that, while the French seemed destined to remain a significant force within the Dominion, they would necessarily be a drop in the ocean in the context of a federal Empire. Canadian imperialists would have the comfort of knowing that they were not citizens of a bi-national country, but citizens of an Anglo-Saxon empire with a small ethnic minority in a couple of its provinces.

It is this aspect of imperial federation in Canada which has not been explored at length: the orientation of Canadian national destiny towards the United Kingdom neither as a counterpoise to Canadian-American relations, as Norman Penlington has suggested; nor as the outward expression of the intricate perceptions of Canadian identity and mission amongst a certain category of Canadians, as described at length by Carl Berger. Rather, it is imperial federation as part of the on-going process of building a British colony not on top of a primitive native population, but on top of a pre-existing European colonial population. In this working out of a modus vivendi, Canadian imperialists hoped that strengthening the British connection, and thereby harnessing British support, would allow British Canadians to dominate the confederation without splitting it along racial lines. This was never likely to be achieved, and since, even today, the emergence of a Canadian policy supported in the Anglophone provinces but widely opposed in Quebec, causes an immediate surge in French separatist sentiment, it is arguable that the true legacy of the UELs is that the country was racially organised in such a fashion as to make majoritarian democracy and national unity hopelessly incompatible. The modern relevance, therefore, of this first attempt to codify and promote a specifically Canadian national identity could not be greater.

CHAPTER III.

FOR MANY FRENCH-CANADIANS, THE IMPERIAL FEDERATION movement, and Canadian imperial sentiments in general, represented an English-Canadian – or more properly a British-Canadian – conspiracy to deny them the bi-racial and bi-cultural country which they had been promised in extravagant terms in every generation since the British conquest of New France in 1759-63. Crucial to such an argument is some consideration of the culture which was believed to be so under threat.

British observers tended to take away similar ideas about the French-Canadians. Sir Charles Dilke, for example, prolific traveller in the British Empire and the United States, noted their demographic origins in Brittany and Normandy, and might have gone on to mention Picardy and the Aunis – regions which have always had a somewhat ambiguous relationship with what one might call la Grande Idée de la France. Indeed, at least one French-Canadian attempt to defend the rôle of Quebec within the Confederation insisted upon the word ‘Celtic’, rather than ‘Gallic’ or even ‘French’, as the adjective for Quebecois culture, as against ‘Anglo-Saxon’ for British Canadian culture. They were, then, hardly what most Victorian Englishmen would have thought of as Frenchmen, but Dilke saw this not as a dichotomy between la Patrie and la Nouvelle France, but between provincial and metropolitan Frenchness, and neatly summed up this ambiguity: “they have not become more Parisian than they were when they left France, although they are not less French”. Moreover, since the expansion of their population was the result of natural growth rather than significant emigration from France, their distinct character and sense of Franco-American identity was not diluted by great influxes of newcomers, as was the case with the United Empire Loyalists who founded British Canada, in spite of their ten-fold increase since the time of the conquest.

In any case, colonial or merely provincial, or indeed both, by the period with which this paper is primarily concerned it was generally accepted that this alien element was unlikely to disappear from Canada, and that their Frenchness, in whatever form it was assumed to take, would not simply go away. It had been expected that they would be absorbed after 1763, in spite of allowing them their own laws and customs, because of exposure to the British example; it rapidly transpired, however, that the Anglo-Saxon alternative did not tempt them. Dilke made various comparisons with the South African Dutch – the only other significant western European colonial population which came to be absorbed into the British Empire. Both were conservative, proud, alien elements within their respective British colonies; neither would co-operate on any basis except British recognition of their institutions and customs; both were prolific breeders; whether Catholic or Calvinist, both peoples’ religions exerted similarly puritanical social pressures on their small, rural and often isolated communities, and, in the case of the Quebecois, the Roman Catholic Church was a stronger presence than in Ireland or even Italy, which promoted and entrenched French-Canadian exclusiveness by discouraging mixed marriages with Anglo-Saxon Protestants.

Importantly, both had similar attitudes towards their respective mother countries, a sort of sentiment without sympathy, probably more deeply ingrained in Quebec because of its antipathy to radical republicanism and atheism. Indeed, the opinions of many French statesmen of the nineteenth century would have found as receptive an audience along the St. Laurence River as would Mazzini’s at the Vatican. No more, one can only suppose, were the Afrikaners of the apartheid period sympathetic to the modern Dutch ideals of the permissive society.

In the case of French Canada, the divergence between Old and New France in the later eighteenth century had two vitally important consequences. The first is that the British conquest of Nouvelle France in 1759-60 assumed an almost providential character, since it saved French Canadians from the horrors of the French revolution and, most centrally, the secularisation of French government, culture and society. What had seemed like a calamity when the gun-smoke lifted from the battlefields of North America at the end of the Seven Years War suddenly seemed like a blessing in disguise. This reinforced the second consequence, which was the emergence of a messianic sense of what French-speaking North America was. The abbé Lionel Groulx was not expressing merely a personal opinion when he wrote, “La France c’est l’Israël des temps nouvaux, choisi par Dieu pour être le suprême boulevard de la foi du Christ venu, l’épée et le bouclier de la justice Catholique. Et…le Canada français est donc héritier des privileges de la mère patrie”.

In short, the sacred torch entrusted by God himself to the French nation had been passed from the hand of the Mother Country to her daughter. It would be hard to overstate the strength of Roman Catholic devotion of many French Canadians. Just over two years before Groulx wrote the passage quoted above, he had been in England seeing a play about Edward the Confessor – his favourite English King because of his canonisation by the Pope and his alleged embodiment of the apex of English Catholicism. He wrote, “Albion en était à son âge de lumière et de foi, et Rome encore la couvrait de son égide immortelle” . Irrespective of the fact that the Danes and Normans were smashing up Anglo-Saxon England at the time, and that this lumière et foi was overshadowed by violence, fear, instability and brutality, the English still looked to Rome for consolation and so were a civilised people still.

The Quebecois were perhaps fortunate in that the first, crucial years after the conquest coincided with a British re-evaluation of their relationship with Catholics and their rôle within the British world system. They were beginning to understand that ‘popery’ could prove a powerful ally of conservatism in an age of innovation and instability. Rather than a hostile fifth column, they might be a bulwark against protestant radicalism in North America, and later against Jacobin radicalism in France. There was in fact a systematic attempt to bring Catholics ‘on side’ between the late eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, with the grant of £9,000 to the Catholic seminary at Maynooth in 1793, the attempt to emancipate Catholics in the Act of Union in 1800-1801, the grant of the franchise in 1829, and the increase of the Maynooth Grant to £26,000 in 1845.

Combined with the increasing experience on the ground of British personnel, particularly Carleton and H.T. Cramahé, this amounted to a “quiet revolution” in British attitudes towards French Canadians. The most significant manifestation of this tendency was the Quebec Act of 1774, which reveals a good deal, not just about the attitudes of British North Americans towards Quebec, since, as argued above, the United Empire Loyalists were not already enemies of the American patriots’ world-view by 1774; but also about the attitude of what might be called the ‘official mind’ in London towards French Catholics within the Empire.

The British colonists had hoped that the Proclamation of 1763 would presage the creation of “another Ireland” in Canada, with a militant Protestant ascendancy ruling over a larger population of papist peasantry. The failure, however, of the Proclamation to secure the mass migration of British Protestants from the south meant that this plan was stillborn. Young, ambitious and unscrupulous merchants and tradesmen from New England had trickled in, and a few Scots back-country traders and shopkeepers had swelled their numbers by a few hundreds. The ministry had no intention of instituting an assembly dominated by a minority of British American protestant fanatics who would probably inspire a Quebecois revolt within weeks, and decided instead to bring the Canadians into the British Empire as more or less equal subjects.

Almost as soon as the news of the Act reached North America, Congress put together ‘a clear idea of the Genuine and Uncorrupted British Constitution, in an address to the inhabitants of the Province of Quebec’ for distribution in Canada. It announced to the Canadians the joy which British America felt when Canada was incorporated into the Empire with its free institutions, and its sadness that the ministry had seen fit to renege on its duty to introduce these free institutions and instead to leave a body of French civil laws. In one of the most remarkable documents of a remarkable period, Congress was straight-facedly trying to incite French Canadians to revolt against Great Britain for maliciously allowing them to keep their own laws and permitting limited French participation on Quebec’s government. Perhaps the British colonists imagined that the Quebecois would respond by petitioning the King not to allow them any quarter until they had come to their senses and become Congregationalists. The end of the letter, however, revealed the real preoccupation of the authors, as they insisted that all these beneficent measures were merely gestures to buy them off, and thus to make Canadians “the tools in their hands, to assist them in taking that freedom from us which they have treacherously denied to you”. The Quebecois, perhaps suddenly coming to believe that London’s assurances of the clemency of British rule had not been wholly false, were unimpressed, seeing this Fides Punica for what it was. Even the appeal to Montesquieu, so much more widely read, in Nugent’s translation, by the more educated and prosperous British colonists than by Canadian peasant farmers, demonstrated how little the British North Americans appreciated their audience.

It is tempting to conclude from this that if, as Oscar Wilde suggested, hypocrisy is the English vice, then the authors of this address were manifestly English at the very moment of their rejection of England. Be that as it may, four years before the controversial Act, civil jurisdiction had been already been returned from Justices of the Peace to the French Courts of Common Pleas; and L.P.M. Deglis, a Catholic priest, had been appointed coadjutor for Quebec to shore up the Canadian episcopacy – the death knell to any dream of establishing a mercantile Ascendancy on the Irish model.

Considering what to do with Quebec had forced Britain to re-evaluate the constitutional attitudes which determined the kind of Empire they wanted. The ministry came round to the opinion that the underlying flexibility of the constitution would allow the Act, whereas British Americans thought that the constitution was fixed and immutable. Subject peoples could be treated in one of two ways. Firstly, they could be deemed fit to enjoy the blessings of the British way of government, which could be expatriated because its freedoms were universally applicable – echoes of which sentiment can be seen in modern neo-conservative American foreign policy. Secondly, as the British began to accept, their histories and cultures might render British-style self-government inappropriate, and their different racial or at least cultural needs acknowledged when devising a government appropriate for them.

Neither of these approaches are beyond criticism: the former because it denies the validity of other peoples’ ways of life, and the latter because it assumes that some races are incapable of governing themselves responsibly. Nevertheless, it marks the earliest divergence between what French Canadians came to expect of the Imperial Government and what British colonists on the spot were willing to allow them – a cleavage which is crucial to the central argument of this paper. They saw their submission as a contract by which they offered loyalty in exchange for national preservation, whereas British North Americans could only see popery established in conquered territory: the victor vanquished.

French Canadians had in fact secured, through dogged determination, the various concessions which enabled them to continue their cultural life. Their intellectual tradition could be presented, with some justice, as stretching from the seventeenth century, which produced the Lettres Historiques and Lettres Spirituelles of Mother Marie of the Incarnation, an Ursuline nun, and Pierre Bouchet’s 1664 Histoire de Nouvelle France; through to the newspaper age, which saw the establishment of the Gazette Littéraire in 1778 in which appeared Joseph Quesnel’s fables, elegies and short poems, of Le Canadien in 1806 and Le Courrier de Québec the following year, and heroic poetry such as Joseph Mermet’s Victoire de Châteauguay which appeared in the Montreal Spectateur in 1813; right up to the Victorian period in which patriotic literature, heralded by F.X. Garreau’s Histoire du Canada of 1845-48, captivated French Canadians, anxious as they were to refute British Canadian claims that the Quebecois had no past.

The desire to establish French Canada as a mature and cultural nation in its own right was taken further by Louis Aubert de Gaspé, whose anecdotal and romantic history, describing the refined and charming nature of the easy, seigniorial social life of Nouvelle France before the conquest may have been dubious, but fulfilled a genuine psychological need for people accustomed to being looked down upon as cultureless peasants by their conquerors. Similarly, Louis Frechette, whose Fleurs Boréales and Oiseaux de Neige established his reputation as a poet in 1880, reassured Quebecois that they were as capable of rendering the French language into beautiful verse as the exquisite exemplars of la mère patrie.

This, almost as much as the True Faith, it was their duty to preserve in the New World. They had already given up much of their sovereignty to the British to preserve themselves from the Americans – the British were bad enough, but their colonists in America did not have even the few trappings of civilisation, such as apostolic succession and landed squires, which their Mother Country had. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, however, imperialism emerged as a threat to their way of life, or so they saw it, every bit as dangerous as absorption into the Manifest Destiny – one which would have just the same devastating effect on the culture which they had struggled so successfully to preserve, and which, for many, it was their sacred duty to preserve as a kind of New Jerusalem.

Particularly galling was the sense that the blow came at the moment of near victory. Their growth, prosperity, everything pointing to “l’avenir brillant” for Quebec; their success in not only avoiding absorption and obliteration in 1867-73 but actually winning a disproportionate influence over the Dominion, much greater than their numbers might warrant; all under threat because the British Canadians felt undermined by the growth and success of French Canada, and sought to harness this moment of popularity for “the federal idea” to create a vast, Anglo-Saxon polity, “combinés en vue de [nous] isoler et de [nous] absorber au milieu d’éléments anglais plus nombreux”, according to Charles Gailly de Taurines in 1891.

French Canadians generally recognised that the British Canadians had never experienced anything so schismatic as their own break with France, and so had a very different concept of what it was to be Canadian. Indeed, their particular foundation myth was predicated on the explicit rejection of colonial independence. Moreover, the constant flow of arrivals from Britain and Ireland maintained intimate relations, in the minds of British Canadians, between the Dominion and the home nations. As a result, “les Canadiens-Anglais sont Anglais d’abord, Canadiens ensuite. Les Canadiens-français…sont Canadiens avant tout”. This naturally tended the former towards pan-saxonisme, which, whether in its American or British Imperial forms, was the most dangerous enemy of Quebec. Like Gailly de Taurines, E. de Nevers agreed that it was the growth and expansion of Quebec which had brought them round to Imperial Federation, as British Canadians began to see their Francophone compatriots as “une injure faite à l’âme de l’Anglo-Saxon…nous sommes une épine cruelle aux flancs du pan-saxonisme”.

De Nevers, however, was more generous than most in ascribing this aspect of Anglo-Canadian imperialism not to Francophobia or ‘no-popery’, but to their peculiar love of order and rationality, the same obsession which had given rise to their bloodless, inhuman, capitalist-individualism. So, even if these federal schemes for imperial unity were not motivated by “un sentiment d’hostilité à notre égard”, they simply did not like the aesthetics of the situation. It was irrational that a people, especially Englishmen, should have to share their territory with foreigners – “Le Province de Québec, le peuple canadien-fançais, leur fait l’effet d’une excroissance désagréable qui gêne leur conception idéale d’unité et d’homogénéité” . Even Henri Bourassa, one of the most prominent of the French opposition writers in Canada and more inclined than most to see treasons, stratagems and spoils, wrote in the Devoir in March 1914 that most British Canadians merely felt that the French, “generally speaking, are a nuisance”.

This, however, was hardly a great deal more reassuring for French Canadians than ascribing the Imperial Federation movement to mere prejudice. Whether motivated by Protestant bigotry or the love of logic and consistency, the objective was still the elimination of the French element as a significant factor in the public and private life of the Dominion. As touched upon above, the Quebecois saw the Quebec Act, the rhetoric of the War of 1812, the Durham Report and the Union of the Canadas, and the articles of Confederation which, in 1866-67, guaranteed the privileges of their provincial legislature, as attempts, whether honourable or merely pragmatic, by the British government to do the right thing by French Canadians in the teeth of fierce opposition by the British colonists on the spot, and believed that Imperial Federation presented an opportunity for Anglo-Canadians to have their way at last – a most sinister attempt to tear up these constitutional arrangements and bury their hard-won privileges in a global Anglo-Saxon federation in which they would be as lost and powerless as they would be in a continental union with the United States.

Bourassa stressed the demographic doom which Imperial Federation spelled for his people: while they were 30% of the Dominion population and frequently held the balance of power in the federal House of Commons, they were “une quantité négligeable dans l’ensemble des possessions britanniqes: 1,600,000 âmes – en comptant les Acadiens des provinces maritimes – isolés au milieu d’une population de 400,000,000”.

As late as the Second World War, one commentator recognised the survival and even flourishing of this British Canadian tendency towards imperialism, and specifically linked it to feelings of discomfort arising, as argued, from the incompatibility of their inbuilt psychological instinct of 200 years’ global supremacy with their having to share power with another people in their own borders. This led to a paranoid fear of losing their majority and control of the reins, and hence periodic calls for British immigration and imperial co-operation: “pour sauveguarder leur suprématie, vous le voyez se cranponner périodisquement à des projets d’immigration britannique massive, mais surtout et toujours l’idée imperialiste”.

Indeed, it was feelings like this which made the British Canadian actually more imperialist even than his cousins in the British Isles, because he was an “imperialiste inquiet”, his racial passions exacerbated by living amongst foreigners. British colonists in Canada – and South Africa – were more inclined to assert their national origins by the mere fact of exposure to a cultural ‘other’, and as often as not this engendered an attempt to “supprimer les diversités”. Imperialism and Imperial Federation, according to this French Canadian model, supplied a psychological crutch to an insecure people.

In short, French Canadians were convinced that the perceived necessity to assert a British nationality took a particular form, viz.- a campaign for political, economic or military integration, and sometimes all three, with other British colonies and with the Mother Country itself, because of a combination of fear and loathing for the French-Canadian enclosure which they had created directly in between their eastern and western provinces. Even some French Canadian nationalists acknowledged the difficulty in which British Canadians were placed by the geographical location of Quebec between Ontario and the British provinces of the coast – any union between the British provinces had to encompass the French one, or it would make no coherent geographical sense: a split between British and French Canada would rupture British Canada itself, as well as the Dominion as a whole.

In other words, geographical reality meant that British North America had to incorporate a non-British territory, but political and cultural reality meant equally that the job of making British North America truly British was unlikely to be achieved freely and democratically within the territory in question, and therefore that the territory in question had to be changed – in short, widened to include more British territories.

It is perhaps interesting to note that, unlike the Cape Dutch, the French Canadians’ tendency was not to implicate the British government in London with this plot, nor the population of the British Isles more generally. To be sure, they associated the capitalist-individualist nexus, “le chacun pour soi”, and the threat which it posed to French Canadian culture, with all Anglo-Saxons everywhere, the British as much as the Americans or the Anglo-Canadians: unlike the more romantic British Canadian imperialists, they seemed aware that the Industrial Revolution started in rural Shropshire, and that England was more the cradle of capitalism than it was the last bastion of social ease, of bishops and marquises and traditional values, as United Empire Loyalist tradition would have it. It was “le mercantilisme anglo-yankee”.

Nevertheless, it is worthy of note that the Quebecois very seldom suggested that British Canadian imperialists were being manipulated from London, like marionettes by their puppet-master, as was so frequently the case in contemporary South Africa. The few lone voices tended to make themselves heard, paradoxically, as the Boer War started to crack the imperial mania, and as yet more terrible events opened the fissures and allowed the waters to pour in and drown the New Imperialism. For example, Bourassa saw Joseph Chamberlain, “le Bismarck anglais”, to be taking advantage of British Canadian loyalty to impose a kind of military federation to assist in his wicked, deceitful war against the Volk. Thereafter, he planned to move by imperceptible stages towards a new imperialist relationship and eventually put constitutional form to his faits accomplis. Indeed, Bourassa believed that these unscrupulous British imperialists won a victory beyond Chamberlain’s wildest dreams, obtaining colonial military assistance with no worthwhile quid pro quo; and even Herbert Asquith came in for criticism, having allegedly bought Canada with “monnaie de singe: décorations, flatteries, avantages personels”.

Still, for most Quebecois the locus of imperialist agitation was in British Canada, and most particularly in Ontario. There, the descendents of the old United Empire Loyalist pioneers had finally seized upon Imperial Federation as a method to deny them their national existence. Only thus could British Canadians “curtail their privileges and bring them under the control of a federal parliament, in which their peculiar interests might be sacrificed and their identity as a distinct race eventually lost”. That French-Canadians believed this is certain: what remains to be seen is whether or not they were right – a consideration which necessitates a closer look at British Canadian culture and politics, and the attitudes and opinions of the leaders of imperialist or imperial federationist thought in British Canada.

CHAPTER IV.

AS DISCUSSED ABOVE, J.E. TYLER’S 1938 WORK DESCRIBED imperial federation as a Canadian response to a crisis coinciding with a similar British response to a different crisis, and that the nature of the Canadian response was to be understood in the context of the United States and of French Canada. In his brief treatment of the second consideration, he describes the Quebecois as introverted, parochial, and consistently opposed to imperial federation when they thought about it at all. Anglo-Canadians assumed, generally correctly, that they were loyal because the only other option was absorption into the Manifest Destiny and the consequent obliteration of their culture, but confidence in a loyalty engendered by fear of the United States was far from universal.

A useful means of assessing the Francophobe element in Canadian imperialism is through the window of the Equal Rights Association, which was established in reaction to the Jesuit Estates Act and was basically a no-popery movement masquerading as an anti-ultramontanism movement. In 1888, Honoré Mercier, Premier of the Province of Quebec, had used the provincial legislature to sell some estates which had been granted to the province in 1830-31 to raise revenues for public education. Before the conquest, they had belonged to the Society of Jesus – the Jesuits – but were thereafter forfeited to the Crown, and held in trust by the government of Lower Canada. Before going ahead with the sale, however, Mercier wrote to the Vatican asking if there were any objections, and in the preamble to the bill undertook to clear any particular sales with the Propaganda and to compensate the Church. The immediate, widespread and implacable backlash in British Canada showed the true colours of many Anglo-Canadians whose prejudices may otherwise have remained under the surface, and perhaps made others think about the question of race in the Dominion in new ways.

As briefly mentioned above, the leaders of the anti-Catholic Association were D’Alton McCarthy, Alexander McNeill, Bishop O’Brien, Tyrrhitt, Clark Wallace and later Colonel Denison. These were, without exception, prominent members of the Imperial Federation League. This raises a series of important questions, especially in conjunction with the consistent French-Canadian belief that British Canadian imperialism was a conspiracy to eliminate the French element in Canadian political life.

In many ways, then, nineteenth century Canada was a “triumph of ideology and politics over geography”, particularly but not exclusively in its separation from the United States. This was made possible – perhaps, indeed, made inevitable – by the Tory tradition of loyal, Protestant conservatism, which proved a fertile breeding-ground for the Orange Order in particular and hardline Protestantism in general. In more ways than one, this was an exact mirror image of French Canadian Catholicism: an explicitly British fusion of religion and politics, and the idea of Providence with a sectarian flavour, emerging in reaction to, and in parallel with, the Quebecois’ supposed destiny to preserve the True Faith in North America from the depredations of heathen Protestants. Put simply, the question being debated was whose Providence it was to be: those who, after the Revolution, sought a corner of North America where His Majesty the King, and His Heirs and Successors, would always be Defender of the Faith; or those who sought to ensure that, in spite of the destruction of Bourbon power on the continent, some corner of North America would always own His Holiness at Rome as arbiter of the True Faith. In some ways, perhaps, Canada’s providential character was stronger for British Canadians than the Quebecois, because of the “mythology of sacrifice” which grew up around the self-imposed exile of the loyalists who refused to live outside the Empire in 1784.

As a result of the importance of Canada as a sanctuary for the threatened British American civilisation, in the minds of many British-Canadians contempt for Catholicism and Frenchness became a sort of patriotic duty – the Loyal Orange Order’s stridency on the subject may have been unusual, but only because it was greater in degree, rather than different in type, from the feelings of ordinary British-Canadians. As late as the 1920s, Stanley Baldwin was able to criticise Andrew Bonar Law’s stance on the Irish Question as having brought too much of the spirit of Orangeism from Canada.

It is interesting to note that the idea of French Canadians as a ‘lesser’ people was expressed in terms which were similar to those used by British colonists elsewhere who were busily engaged in displacing indigenous populations. Indeed, the French and Native American peoples of Canada were often explicitly equated. The treason of French priests and “French half-breeds” was contrasted with the loyalty of “Scotch half-breeds” in the Red River Rebellion. Speeches in Toronto immediately after the rebellion in winter 1869 merely called the Métis “the French at Red River”, and noted that French Canadians from Montreal and Quebec “have an aptitude for falling into the modes of savages”. Monsieur Lefroy, the only French Canadian in Charles Mair’s Tecumseh, a drama about the clash of Briton, American and Native American in the Great Lakes country, is equally the only ‘Indophile’ to be found amongst the dramatis personae. He is ‘native’ to Canada in the same way as Chief Tecumseh and his daughter, to whom Lefroy wishes to be married, and is thus associated with unreason, darkness and barbarism. Even their population expansion was snidely attributed to the inability to restrain their appetites which one might expect from such a child-race: “considering the prolific habits of the French Canadian peasantry, [Canada’s population] should stand higher from natural increase alone”.

Patronising, prejudiced, bigoted, and even a little afraid – the attitudes of many British North Americans seemed not to have changed since Benedict Arnold abandoned his erstwhile comrades in fury at the alliance with France. Bourassa even believed that some British Canadians sometimes pretended to be imperialists just to show their distain for things French: “ils s’abstiennent souvent d’exprimer leurs objections à imperialisme ou leurs veléités d’indépendence, par la seule crainte d’être confondus avec les beastly French”.

Some of the most rabid anti-Catholic tracts one might hope to find – or dread to find – were penned by Canadian imperialists, often, but not always, anonymously, and can be found courtesy of the Willard Tract Depository in Toronto. One, at the height of the Jesuit Estates controversy, believed that “Pope Leo XIII… [is] Governor General and Chancellor of Canada’s exchequer”. It was absurd, the author went on, that the Protestant majority should have to beg their Protestant government for equal rights with papists – if the Quebecois must assert that Jesuitism was a legitimate offspring of Catholicism, then this was a reason to attack Rome, not to leave Jesuits alone. Catholics were guilty of “heinous crimes and worse doctrines…dark, benighted, covetous, false, bloodthirsty, ignorantly superstitious, and anti-Christian”. Thus they had forfeited all their rights in British dominions, and the Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, should be horsewhipped for conniving with traitors. Anti-popery was not intolerance, but merely the refusal to tolerate Catholic intolerance, and impatience with the “known characteristics of the Roman Catholic religion to be not only aggressive, but encroaching”.

Importantly, deranged though this author may have been where Roman Catholics were concerned, his first and only suggestion to neutralise this fifth column was enthusiastically imperial. There “ought to be…[a] Code Victoriana” for citizens of the British Empire, what the Code Napoleon was to France and the canon law of the Jesuits was to the Catholic Church: England and Canada should come together to face the same threat under “the Confederate Union Jack”.

Nor was it only the usual suspects who took this view – they merely expressed it more vehemently. Some serious commentators took up the theme. The Canada Law Journal for the first quarter of 1889 contained an article on ‘The History and Mischief of the Quebec Jesuit Estates Act’, which claimed that the legislation revealed “more fully than anything published in the English language has hitherto done, the sort of religious and political Frankenstein which our forefathers unwittingly created at the capitulation of Quebec, and which now, in so many ways, blocks the path of progress in the Dominion”. The French element, by delegating the distribution of British money to a foreign potentate, had shown itself to be “a menace to the integrity of the British Empire”. Even Colonel Denison, who once said of Orangemen, “God help Protestantism in Canada if it has to be defended by that contemptible trash”, was inclined to see “a secret Jesuitical plot”.

It was not, then, only French-Canadians who noticed the potential of imperial integration to tip the Canadian racial balance in the Anglo-Canadians’ favour. D’Alton McCarthy, Tory MP, Irish Protestant and Orangeman, and inaugurator of the Imperial Federation movement in Canada in 1885, was moved by the passage of the Jesuit Estates Act, by which “Her Majesty’s name is thus to be trailed into the dust”, to list the easy victories which the French Catholic sectarian interest had won in Canada: freedom of religion in 1763; permission to charge tithes and use French civil law in 1774; a legislative assembly, although conducting business in English, in 1791; French permitted in 1840-41; French recognised throughout Canada in 1867; and asking the Pope to administer Crown property in 1888. Wondering where it would end, he accepted that annexation to the USA would “bury the Frenchmen”, but preferred a British solution.

The Equal Rights Association, he went on, was not formed specifically to oppose the Jesuit Estates Act, but to make plain the cunning manipulation of the French-Canadian bloc in the public life of the Dominion, and to encourage British Canadians to seek to ‘bury’ them in Greater Britain rather than the United States. For, “We must not forget – I am afraid that some of my friends from the province of Quebec do sometimes forget – that this is a British country”.

It is interesting evidence that public debate in Quebec seemed not only to have taken the Act in its stride, but also to be blithely unconcerned about the mass hysteria which it had engendered in British Canada. Some attempts to refute the Equal Rights Association’s claims were made, notably by Louis Georges Desjardins and, in a series of letters to the Star, Premier Mercier himself. Nonetheless, an opposition manifesto for Quebec’s provincial election in 1890 went into obsessive length about the shortcomings of Honoré Mercier, but not once did it mention the racial tensions which had been stirred up by this “régime désastreux”. They seemed overwhelmingly concerned with financial incompetence, even incontinence, than constitutional and racial issues, furnishing long and detailed lists of the extravagant augmentation of Monsieur Mercier’s expenses, criticisms of the public debt and of feeble negotiating for the printing contract for $3.5 million with a company in New York, in spite of his promise to manage the economy with rigor if elected. There is only a dry passing reference to “les nombreux scandals commis par le ministère”, which could in fact refer to almost anything.

Indeed, the Act, by drawing attention to this fact that the Quebecois’ and the British Canadians’ political discourses existed in almost complete isolation from each other, had resurrected the debate on the Anglicisation of the Quebecois – an issue which had lain dormant for at least twenty years. Old men in Ontario began once again to remember that Canada was British by conquest, that the French Canadians had subsequently been protected by treaty, and begin to think that “there has been a constant effort on the part of French Canadians principally, to misrepresent and distort and create false impressions…as to the terms of that treaty”. The Proclamation of 1763 had said nothing about their language – only their religion and their laws, as far as they did not oppose British law. Now, the political interference of the Roman Church was being presented as the expression of religious liberties and therefore as a subject for private conscience which must be allowed by the Confederate government.