[+] HONOURING OUR PATRON, SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL, VICTOR OF THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING PEOPLES

[+] HONOURING OUR QUEEN, ELIZABETH THE SECOND, ON THE 80TH YEAR OF HER BIRTH (1926 - 2006)

[+] HONOURING OUR KING, SAINT EDWARD THE CONFESSOR, ON THE 1000TH YEAR OF HIS BIRTH (1005 - 2005)

[+] HONOURING OUR HERO, LORD NELSON, ON THE BICENTENNIAL OF THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR (1805 - 2005)

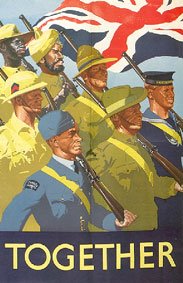

[+] HONOURING OUR SONS, THE QUEEN'S COMMONWEALTH SOLDIERS KILLED IN THE 'WAR ON TERROR'

[+] HONOURING OUR VETS ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE VICTORIA CROSS (1856 - 2006)

This essay by John Fox (our very own William Pitt) was the winning entry in the New Zealand based Maxim Institute’s 2004 competition. Taking as their starting point Sir Isaac Newton’s proposition, “If I have seen further than others, it is because I have stood on the shoulders of giants”, entrants were asked to consider how our present culture, laws, institutions and values are built upon the ideas of the past. What role does Civil Society play in preserving and passing on heritage? Can progress and preservation of virtues in society co-exist?

“The mark of insanity is reason without a root, reason in a void.”

-- G. K.Chesterton, Orthodoxy

“In this Voyage of thy Life, hull not about like the Ark without the use of Rudder, Mast or Sail, and bound for no Port. (Rather) let iterated good Acts and long confirmed habits make Virtue a most natural or second Nature to thee.”

-- Sir Thomas Browne, Religio Medici, 1635

Karl Marx wrote, “A people without heritage are easily persuaded”. Tradition, wrote Edmund Burke, is “our anchor”. In this instant age, in which individualism and relativism hold sway, we have lost sight of the important role that our ancestors, their experience, and their institutions can play in the fabric of Civil Society. By abandoning our heritage in favour of transient ideological fashion, we have lost sight of the concept of true progress, substituting for it an unrealisable utopian ideal, based on relativism, which, while pretending to exalt man, degrades and destroys him.

Karl Marx wrote, “A people without heritage are easily persuaded”. Tradition, wrote Edmund Burke, is “our anchor”. In this instant age, in which individualism and relativism hold sway, we have lost sight of the important role that our ancestors, their experience, and their institutions can play in the fabric of Civil Society. By abandoning our heritage in favour of transient ideological fashion, we have lost sight of the concept of true progress, substituting for it an unrealisable utopian ideal, based on relativism, which, while pretending to exalt man, degrades and destroys him.A proper appreciation of tradition, heritage and historical institutions is a vital part of the foundations and maintenance of Civil Society. Recognising the role of tradition in the creation of institutions that maintain social order is tremendously important. Civil Society plays an important role in the preservation of heritage; by heritage virtue; and by virtue, true progress. I shall briefly examine the importance of tradition to Civil Society: as a source of experience, as a creator of institutions, and as a source of inspiration.

It has become fashionable to act as if the 21st century is somehow more enlightened than previous centuries. This is particularly the case in so-called “progressive” politics, which seeks to “liberate” society from what Thomas Paine called “the manuscript authority of the dead.” In his frenzied response to Edmund Burke, Paine put it this way: “The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man; neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow.” By this thinking, the “competence” of the present generation is enough to over-rule the traditions of all the previous ones. This view is alive and well in New Zealand. MP Moana Mackey said of marriage and Civil Unions: “One (marriage) has behind it thousands of years of interesting tradition and history; the other’s history begins here today.” That is, the competence of this generation is enough to “change” marriage, and the traditions of our forefathers are merely “interesting”. In the light of this philosophy, it is important to examine the arguments for the continuation of tradition.

Its first importance is as a source of experience. St Cyprian wrote, “Art thou unsure as to a matter? Let the Fathers be asked.” Tradition is a treasury that must be consulted, so that in our moral and social decisions we are not guided simply by fashion, but by a deep sense of what it is to be a moral human. Chesterton called this moderating influence “the democracy of the dead.” People in the seven millennia of recorded history struggled with the same issues we do. A simple example of the commonality of human nature across time can be found in famous “youth of today” quotations: “The young people of today think of nothing but themselves. They have no reverence for their parents or old age. They are impatient of all restraint” (Peter the Hermit, 1100 AD). “Our young men have grown slothful,” wrote Seneca in the 1st century AD. “I see no hope for our people in the youth of today,” wrote Hesiod in 8 BC. Across time and culture, humanity wrestles with the same problems. The restraint of power. The promotion of public virtue and suppression of vice. The education of the young. It is madness to have available records of solutions tried, failed, discarded, adapted over thousands of years and not use them. “We (should be) afraid to put men each on his own private stock of reason; the stock in each man is small. The individuals would do better to avail themselves of the capital of nations and of ages.” When we destroy the institutions of our fathers, we will have all their work to do again.

Our ancestors did not randomly associate in political arrangements. Our parliamentary system, our moral and legal codes are the result of thousands of years of distilled experience. Our institutions are organically grown from the trials, tribulations and experiments of our ancestors. They were not imposed from above to recognise created rights, but grew from below as recognitions of rights already existing. For instance, the right of trial by jury was created because our ancestors saw that a man could not impartially judge his own cause. The Petition of Right of 1688 and the Act of Settlement of 1701 state, “Whereas experience hath shewn”, and go on to recognise the fundamental rights of British subjects, rights which form the basis of our legal system. Institutions like Parliament, the law, the freedoms of religion and so on are thus all recognised not only by law but developed by tradition, rooted firmly in the village green. It is these traditions which progressivism as a philosophy seeks to challenge, not on the grounds of reason, but of ideology. The Privy Council, for instance, is “anachronistic” in the present government’s view, not because it fails to deliver a high standard of impartial justice but because it is a symbol of our dependence on the United Kingdom, which the government rejects as “infantile”. Progressivism hates the institutions of organic tradition because, as C.S. Lewis puts it, “they give the individual a standing ground against the state.”

Heritage also produces inspiration and identity. The proper appreciation of heritage inspires us to take up the trust given to us by our fathers and make it our own. In the proper teaching of not only New Zealand but also British history we will find an appreciation for our institutions, and the inspiration we need to defend them. Spenser recognised the value of heroes when he wrote, “It is better to teach by example than by rule.” Civil Society has always recognised a life well-lived when it saw one; it has been left to the cynicism of our modern age to turn from praising exemplars of faith, courage and fortitude to cynicism and sniping. Since we have abandoned virtue as an objective standard, we rush to declare the virtuous of yesterday to be villainous, and the villains heroes. We now have books like The da Vinci Code and films which portray Churchill as a drunk, and Austen (or even Queen Victoria) as lesbians. We have begun to revise history in our own image, one which cuts heroes down to size and exalts in feet of clay. This is only possible, of course, because of the widespread ignorance of actual history in our society. As The Screwtape Letters have it: “We have arranged it so that no-one reads old books any more, and those that do are precisely those who get no benefit from them.” The popularity of films like Spiderman or Hornblower shows precisely the longing for heroes which is deep in the heart of everyone. In a classical framework, historical heroes would fill this void. Without tradition, it is filled by the “competence” of this generation: gangs, gangsta rappers and film stars. Without tradition, identity fails and is replaced by alienation and despair.

The simply ancient is not the source of Edmund Burke’s “anchor”, however. It is, rather, a sense of the moral law which the institutions formed by tradition give us. As Burke puts it: “We have implanted in us ideas, rules, of what is just, fair, honest, which no political craft, nor learned sophistry, can entirely expel from our breasts.” It is a connection with the moral law that our traditional institutions give us, a connection with an external standard. Certain things are implanted, transmitted and recognized by our institutions as a vital part of our heritage. Actions are “virtuous” because they conform to the external standard of absolute morality, which we have received. Whatever the origin of the standard, it binds us, and it is transmitted by traditional institutions. This is not to say that all traditions are, ipso facto, virtuous. But tradition, because it is made up of people, is the story of our engagement with the moral law. Tradition thus enhances and sharpens the moral tools for discernment of good and evil, and our traditional institutions have an integral part to play in learning virtue. We have embraced relativism, which judges moral issues as simply a matter of preference and feeling. In this, we have parted company with several millennia of tradition, in which virtuous actions were virtuous not because they were convenient, but because, as Plato put it, they conformed to the “eternal form” of virtue.

It is the business of a Civil Society to transmit virtue to its citizens, to encourage them to conform their conduct to the moral law. This is done in all three spheres of traditional institution—namely, in the civil government through the law and education; in the family through the transmission of values and modelling of standards of conduct; and in the religious sphere. When all three institutions work in harmony, the moral law is tied into a coherent values system. The weak are protected. The strong are restrained. When they are in competition, the moral fabric of Civil Society begins to unravel. Many times the traditional spheres have not always practised the moral law, but they all recognised it. It has been left to the last 100 years to unravel all three. The civil authorities now see themselves as, “Not in the business of Victorian morality.”

We have a values-neutral government. This departure from the moral law has produced a laissez-faire attitude to what used to be called vice, and has resulted in the government deciding moral issues not, as traditionally, on the basis of morality, the common good, or even the views of the people, but on the basis of an ideology of individualism. Without an external standard, all things are permissible. Likewise, the education system, which classically was concerned with promoting virtue in the hearts and minds of the young, has come undone. The Ministry of Education states that both morality and educational quality “vary with context”. Traditional criteria, as found in the Rhodes Scholarship, carry the ring of another moral age: “Truthfulness, courage, devotion to duty, sympathy for and protection of the weak….; exhibition of moral force of character and of instincts to lead” are out, and “tolerance, respect for others, and a good sense of self” is in.

Similar considerations apply to the family. The Pope has restated that which our ancestors took for granted: “The family is the basic cell of human society… it is there that children best learn the dispositions and skills which they require, (There) they best learn the truth of what it means to be a person…challenged by rights and duties.” It is a measure of how far we have drifted from our moorings that despite our horrendous rate of family breakdown, the Pope was attacked as “intolerant of differing ways of doing family” by several members of the government.

Progress and tradition are often seen to be opposed, but they are not. T. S. Eliot responded to the claim that “We know more than our ancestors did” with the answer “and they are that which we know.” That is, tradition is and ought to be living. Progress comes from what Eliot called “the historical sense”, an awareness that “We are not the owners of the earth, but are trustees with life-renewing lease.” Tradition thus can only be renovated when it is understood. It is by proceeding “upon the principle of reverence to antiquity analogical precedent, authority, and example” that we may find a way forward. What does this mean in practice? Take the Privy Council. Our ancestors retained the right of appeal to the Privy Council in order to give us distance from local affairs, and impartial justice and experience. By preserving these things, our ancestors protected the rule of law from corruption. The government’s reform, in abolishing a traditional institution, ought to have at least secured the benefits which tradition offered in its alternative model. It does not.

Ideology divorced from virtue and tradition is brutal, and draws on a destructive utopian tradition which devalues the human person. To renovate a traditional institution, whether it be the family, the courts, or the schools, one must first have an understanding of its purpose. Too often, liberalism has not only a relativistic morality, but an agenda for the traditional institutions at variance with their original purpose. For instance, the traditional purpose of marriage is set out in the Book of Common Prayer : the procreation of children, to avoid fornication, and mutual comfort and help. This institution has been hallowed by 5000 years of tradition. When one examines the reasons for change, they take no account of the first two purposes. They ignore the procreation of children by saying that children don’t need a mother and father and do just fine in “alternative families”. There is no reference to the monogamous nature of the union, since the government is no longer in the business of Victorian morality. Only “mutual comfort and help” is referred to, and it is only this “purpose” of marriage that the law will now recognise. Conversely, when one speaks from within a tradition, as did Newton, one is in a position to critique its bad points, point out changes in “sovereign circumstance”, and to hand on to the next generation a greater tradition than one has received. As Chesterton puts it, “with a fixed heart, we have a free hand.” Without one, we can no longer be free, and we cannot have real progress. We are not only no longer right judges of tradition, we are no longer able to judge value at all.

The challenge of our generation is ably phrased by William Pitt, who said: “Let us examine what is left, with manly and determined courage. The misfortunes of individuals and kingdoms that are laid open and examined with true wisdom are more than half redressed.” It is the challenge of “examining (and rescuing) what is left” which confronts us today. The future of our country depends upon our response.

POSTED AT MY BEHEST WITH KIND PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHOR, WILLIAM PITT THE YOUNGER