[+] HONOURING OUR PATRON, SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL, VICTOR OF THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING PEOPLES

[+] HONOURING OUR QUEEN, ELIZABETH THE SECOND, ON THE 80TH YEAR OF HER BIRTH (1926 - 2006)

[+] HONOURING OUR KING, SAINT EDWARD THE CONFESSOR, ON THE 1000TH YEAR OF HIS BIRTH (1005 - 2005)

[+] HONOURING OUR HERO, LORD NELSON, ON THE BICENTENNIAL OF THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR (1805 - 2005)

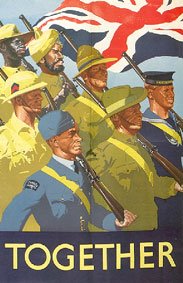

[+] HONOURING OUR SONS, THE QUEEN'S COMMONWEALTH SOLDIERS KILLED IN THE 'WAR ON TERROR'

[+] HONOURING OUR VETS ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE VICTORIA CROSS (1856 - 2006)

Three-hundred and sixty-five days of pro-monarchy bias on this blog each year is probably not really fair to the republicans. So I tell you what: I'm going to break protocol here and allow one of those days to be devoted to the other side. But not just any poor-spirited republican; only the very best will do. No one is better in my opinion than the great contrarian writer, Christopher Hitchens, the anti-religious zealot, British-born and British-accented American, who also happens to be a staunch supporter of Bush's war against - as he calls them - the Islamo-facists. (It fits in with his crusade against religion in general). To put it gently, Mr. Hitchens has a formidable pen and debating style; you cannot but admire someone who can take on William F. Buckley in a debate, while remaining intellectually honest to his Trotskyite ideals (his "better Red than dead" nonsense, and all that). He is absolutely fearless in the face of self-made controversy, witness his famed tyrade against Henry Kissinger, who he unsuccessfully provoked into suing him in the hopes of establishing an official forum to defend his Chomskyesque charge that Kissinger was guilty of crimes against humanity during the Vietnam War, nevermind his total chutzpah against Mother Teresa, a person who, in his opinion, was a genuinely wicked woman.

The following review on William Shawcross' "Queen and Country" was written by Hitchens for the Los Angelous Times almost three years ago to the day (May 5, 2002). I offer it once again as a tribute to my unworthy foes in the republican camp who, when not lacking in intelligence, are still basically a booring squaresville bunch committed to a booring squaresville future. Christopher Hitchens, never the boor, notwithstanding of course.

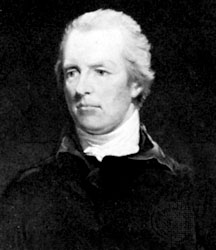

William Cobbett, a great English radical, dryly observed more than a century ago that there was something absurd in a system that referred to "the national debt" and "the Royal Mint." Thomas Paine, one of our less-acknowledged Founding Fathers, pointed out that a hereditary head of state made no more sense than a hereditary mathematician. The sheer, obvious rationality and justice of this critique is countered, by partisans of royalism, with numinous claims about the need for magical and mystical authority; for something to lift our everyday politics out of the drudgery of mere administration. "Fairy tale" is a term often employed (and rightly in my view, since I scorn to conceal my prejudice) by monarchists themselves.

A serious defense of monarchy or of a monarch might begin by recognizing this essential difference in approach. To take only a recent instance, the death of the queen mother provoked the writing of literally hundreds of valedictory articles, all of which dwelt on the supposedly gallant way in which she had visited bombed-out slum dwellers during the Nazi blitzkrieg. None of these moist tributes mentioned the unswerving support that the old lady and her husband, King George VI, had given to Neville Chamberlain a couple of years earlier. Now, "fairy tales" require that the emphasis should fall only on the first anecdote. But elementary journalism, to say nothing of scholarship, requires that the second point be noticed at least in passing. William Shawcross' "Queen and Country" simply omits it, along with much else.

I pause here to note another claim made by monarchists: that royalty provides a context of historical continuity and teaches the value of tradition and the past. This lofty objective is not to be accomplished by such air-brushing. In 1988, the tercentennial of the Glorious Revolution, which brought the ancestors of the current Windsor dynasty to power, there was a celebration in Westminster Hall--the same place where the queen mother's body lay in state. Anyone who has been to that great hall knows that it features a plaque commemorating the occasion in 1649 on which Charles I was tried there for crimes against humanity and lost his head on the wicked and fallacious proposition of the "divine right of kings." But during the 1988 festivities, this plaque was covered with a velvet cloak, as if the British lived in some Stalinist "people's democracy" or banana republic. Shawcross' courtier-style volume is in the same tradition.

It may or may not be true that royalty provides glamour, stability, pageantry and all the rest of it, rather than a wearisome parade of tax-dodgers, unexciting adulterers, chinless princes and frumpish ladies of the bedchamber. But the first belief, if only in the recent and glaring light of the second, does require a little argument. I was continually amazed by the flat, un-ironic, orthodox way that Shawcross relied upon mere assertion: The royal family is a force for political legitimacy. It does have the right to run the national state-supported church. It has enshrined itself in the hearts of a grateful people. Moreover, every gesture made by a monarch is either charmingly informal ("just like the rest of us") or magnificently regal ("the royal touch"). This does occasionally--no, make that repeatedly--become plain ridiculous:

"The Queen's faith has supported her throughout her reign in a job that is very isolating. In 1947, during the royal trip to South Africa, her father turned to Field Marshal Smuts and said, 'There she goes, alone as usual, an extraordinary girl.' It is a theme that painters such as Annigoni have picked up on. In his lovely 1954 painting he portrayed her standing quite alone."

Where to begin? In 1947 she was not yet queen (as her father's contemporary comment suggests). She has never taken a step, even as princess, without an enormous retinue of servants. And, despite the suggestion that Annigoni was on to something unheralded, most people do tend to sit for their portraits unaccompanied. Indeed, the word "portrait" rather implies a study of an individual. But our author is so awash in sycophancy that he cannot venture upon the most banal story without investing its object with quasi-supernatural properties. Indeed, he doesn't even bother to register the fact that a monarchic position, supposedly conferred by exclusive breeding, is by its own definition "sole." It's not dignified for a courtier to bow once to contradiction and once to tautology and then to collapse in a heap between the two.

Nor does Shawcross notice how often he contradicts himself. Describing the way in which the queen and the queen mother colluded with the archbishop of Canterbury and the prime minister to deny the late Princess Margaret the right to marry a divorced man, he writes that "in those days even the innocent party to a divorce was cold-shouldered." Only one page later, he records that the highly popular Daily Mirror conducted the first "royal poll" ever carried by a newspaper, asking its readers "if they thought the couple should be allowed to marry. The vast majority of the respondents were in favor." So what happens to his first assertion? In translation, it becomes his unexamined excuse for the extreme cruelty with which Buckingham Palace wrecked the lives of two people, in the cause of the fusion of church and state and in the name of "family values" that, it now turns out, few of the sulky royal brood seem able or willing to maintain.

In earlier days it was believed that the affliction of scrofula ("the King's evil") could be cured by a touch from the reigning monarch. (The great loyalist Dr. Samuel Johnson was taken to be "touched," but it didn't work for him.) Nowadays, this superstition seems to operate in reverse. Ted Hughes and Andrew Motion were quite good poets before they became poets laureate and began to write abject piffle in praise of the throne. Shawcross was an outstanding reporter and human rights champion before he took on this knee-weakening assignment. One day he will wake up, shake himself and realize that the attempt to breed a ruling family is as silly, and in some ways as sinister, as the attempt to breed a ruling race. Meanwhile, Paine's struggle against the Hanoverian usurpers has only, so far, been victorious in the former American colonies, where the descendants of George III are viewed with proper affectionate condescension as archaic celebrity freaks.