[+] HONOURING OUR PATRON, SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL, VICTOR OF THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING PEOPLES

[+] HONOURING OUR QUEEN, ELIZABETH THE SECOND, ON THE 80TH YEAR OF HER BIRTH (1926 - 2006)

[+] HONOURING OUR KING, SAINT EDWARD THE CONFESSOR, ON THE 1000TH YEAR OF HIS BIRTH (1005 - 2005)

[+] HONOURING OUR HERO, LORD NELSON, ON THE BICENTENNIAL OF THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR (1805 - 2005)

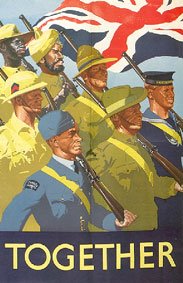

[+] HONOURING OUR SONS, THE QUEEN'S COMMONWEALTH SOLDIERS KILLED IN THE 'WAR ON TERROR'

[+] HONOURING OUR VETS ON THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE VICTORIA CROSS (1856 - 2006)

The governing Liberals lost a confidence vote in the House of Commons today. This means that they have lost the short game, for even if they refuse to resign today or tomorrow, Parliament is now completely dysfunctional and they know it. An election is looming. The longer game is of course another matter, but I have a strong hunch we're in for another match of King-Byng:

The election of 1925 (2005) did not give McKenzie King (Paul Martin) the result he was after. The Conservatives, under Arthur Meighen (Stephen Harper), won the day (114 seat to 102) but not the government. Governor-General Julian Byng (Adrienne Clarkson) instead asked King (Martin) to form a government with the help of the Progressives (NDP).

Months later the coalition fell apart and King asked Byng to dissolve Parliament. Byng refused, citing the fact that Meighen had won the last election, and out of fairness should be given the opportunity to form a government. Well King got all uppity and huffed and puffed that only Liberals have the God-given right to govern Canada (some things just never change), as you can plainly sense from the following testy letter to Lord Byng, the Viscount of Vimy, the general who commanded the Canadian Corps at Vimy Ridge. I think we can chuckle in satisfaction knowing what the good general must have thought as he read the following impertinent letter addressed to himself: "why you lowly snivelling politician, where were you when the boys were dying at Vimy. How dare you lecture me!"

Letter from William Lyon Mackenzie King to Governor-General Byng, 28 June 1926

Your Excellency having declined to accept my advice to place your signature to the Order-in-Council with reference to a dissolution of parliament, which I have placed before you to-day, I hereby tender to Your Excellency my resignation as Prime Minister of Canada.

Your Excellency will recall that in our recent conversations relative to dissolution I have on each occasion suggested to Your Excellency, as I have again urged this morning, that having regard to the possible very serious consequences of a refusal of the advice of your First Minister to dissolve parliament you should, before definitely deciding on this step, cable the Secretary of State for the Dominions asking the British Government, from whom you have come to Canada under instructions, what, in the opinion of the Secretary of State for the Dominions, your course should be in the event of the Prime Minister presenting you with an Order-in-Council having reference to dissolution.

As a refusal by a Governor-General to accept the advice of a Prime Minister is a serious step at any time, and most serious under existing conditions in all parts of the British Empire to-day, there will be raised, I fear, by the refusal on Your Excellency's part to accept the advice tendered a grave constitutional question without precedent in the history of Great Britain for a century, and in the history of Canada since Confederation.

If there is anything which, having regard to my responsibilities as Prime Minister, I can even yet do to avert such a deplorable and, possibly, far-reaching crisis, I shall be glad to do so, and shall be pleased to have my resignation withheld at Your Excellency's request pending the time it may be necessary for Your Excellency to communicate with the Secretary of State for the Dominions.

Letter from Governor-General Byng to William Lyon Mackenzie King, 29 June 1926

I must acknowledge on paper, with many thanks, the receipt of your letter handed to me at our meeting yesterday.

In trying to condense all that has passed between us during the past week, it seems to my mind that there is really only one point at issue.

You advise me "that as, in your opinion, Mr. Meighen is unable to govern the country, there should be another election with the present machinery to enable the people to decide". My contention is that Mr. Meighen has not been given a chance of trying to govern, or saying that he cannot do so, and that all reasonable expedients should be tried before resorting to another Election.

Permit me to say once more that, before deciding on my constitutional course on this matter, I gave the subject the most fair-minded and painstaking consideration which it was in my power to apply.

I can only add how sincerely I regret the severance of our official companionship, and how gratefully I acknowledge the help of your counsel and co-operation.

Letter from Governor General Byng to Mr. L. S. Amery, The Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, 30 June 1926

As already telegraphed, Mr. Mackenzie King asked me to grant him dissolution. I refused. Thereupon he resigned and I asked Mr. Meighen to form a Government, which has been done.

Now this constitutional or unconstitutional act of mine seems to resolve itself into these salient features. A Governor General has the absolute right of granting dissolution or refusing it. The refusal is a very dangerous decision, it embodies the rejection of the advice of the accredited Minister, which is the bed-rock of Constitutional Government. Therefore nine times out of ten a Governor General should take the Prime Minister's advice on this as on other matters. But if the advice offered is considered by the Governor General to be wrong and unfair, and not for the welfare of the people, it behoves him to act in what he considers the best interests of the country.

This is naturally the point of view I have taken and expressed it in my reply to Mr. King (text of which is being telegraphed later).

You will notice that the letter in question is an acknowledgement of a letter from Mr. King (text of which is also being telegraphed later) appealing that I should consult the Government in London. While recognising to the full help that this might afford me, I flatly refused, telling Mr King that to ask advice from London, where the conditions of Canada were not as well known as they were to me, was to put the British Government in the unfortunate position of having to offer solution which might give people out here the feeling of a participation in their politics, which is to be strongly deprecated.

There seemed to me to be one person, and one alone, who was responsible for the decision and that was myself. I should feel that the relationship of the Dominion to the Old Country would be liable to be seriously jeopardised by involving the Home Government; whereas the incompetent and unwise action of a Governor General can only involve himself.

I am glad to say that to the end I was able to maintain a friendly feeling with my late Prime Minister. Had it been otherwise, I should have offered my resignation at once. This point of view has been uppermost in my mind ever since he determined on retaining the reins of office (against my private advice) last November. It has not been always easy but it was imperative that a Governor General and a Prime Minister could not allow a divergent view-point to wreck their relationship without the greatest detriment to the country.

Mr. King, whose bitterness was very marked Monday, will probably take a very vitriolic line against myself -- that seems only natural. But I have to wait the verdict of history to prove my having adopted a wrong course and this I do with an easy conscience that, right or wrong, I have acted in the interests of Canada, and have implicated no one else in my decision.

I would only add that at our last three interviews I appealed to Mr. King not to put the Governor General in the position of having to make a controversial decision. He refused and it appeared that I could do no more.